Yeast storage | Yeast rehydration | Yeast inoculation for white wine | Yeast inoculation for red wine | Some Yeast FAQ's | Lalvin yeasts | Yeast inoculation for red wine

A Wine Yeast Guide

|

| 1930 Print Vineyard Grape Wine Fall Landscape France Winery Benezit Yeast Italy Original Color Print |

What does yeast do?

Yeast is responsible for converting the sugars in the fruit to alcohol, and carbon dioxide gas is given off at the same time. This process is called fermentation.

It is very important to use the highest quality yeast in your winemaking. Yeast does all the work of converting the initial sweet must into great tasting wine in a remarkable process. I can recommend using Lalvin wine yeast made by Lallemand from experience. They are the world's largest producer of specialty wine yeasts, and produce over 100 different wine yeast strains for the professional winemaker in active dried form, and many of these are available to home winemakers in smaller sachets as well.

Many of Lalvin's yeasts are only sold in commercial quantities of 500 mg or larger which are not really intended for home use. Therefore, it could be feasible for a winemaking club's members to pool their resources and purchase a quantity, then divide it up among themselves. Alternatively, one could check the commercial wineries in their area and determine whether they would sell a small quantity of yeast if they happen to be using one of these.

The finest wines are made using only the finest ingredients, so when it comes to yeast most winemakers prefer to use Lalvin dried wine yeast. If you're making wine, you want the best. Please use the chart below to help you choose the proper yeast for your application.

Yeast Storage

Dry yeast can be refrigerated or frozen for greater stability during long term storage. Allow cold yeast packages to reach room temperature then rehydrate as directed for use.

Refrigerated: 4°C

Frozen: -12°C

If yeast packages go past their best-before dates, be wary as they may well be totally inactive when you commence rehydration. It is always good practice to use new batches of yeast rather than try to re-use part packs to save money, and In the long run your ferment will suffer and you may even experience a stuck fermentation - don't let that happen!

Yeast Rehydration

For yeast cells to restore their function they must re-absorb all of their cellular water. This is the most critical phase of rehydration when using cultured dry yeast. Proper rehydration ensures healthy cells which will retain good fermentation characteristics.

When dry yeast comes into contact with water or other liquid solutions, the cells rehydrate, absorbing the wanted water within seconds. However, if rehydration in not properly carried out, the yeast will lose its viability and the remaining populations will not be able to initiate a speedy fermentation. It will be difficult to disperse the yeast as the granules will clump and stick together.

It may be preferable to rehydrate in pure water rather than in must, but I would always choose the latter as the must contains plenty of sugar which improves dispersion. However, if the must contains SO2 or residual fungicides which could be damaging during the rehydration stage, rehydrate only using 1:1 pure water mixed with must. Once rehydrated the cells can resist SO2 and low fungicide concentrations, but not during water uptake.

Quantity of yeast to use:

Recommendations vary but a viable density would normally be obtained by using 25 grams of dry yeast for every 100 litres of must (25g/hl - 25 grams per hectolitre or 100 litres).

- A higher yeast density should be used if the grapes are in not in good condition.

- A cloudy must at 10°C which is high in SO2, may need 50g/hl.

- A clean must at 15-20°C might only require 10-15 g/hl.

- Low inoculation can result in a long lag phase, and can allow unwanted, natural yeasts to multiply.

- High inoculation rate has no detriment apart from a higher cost.

Volume of water to use:

A guideline figure would be to use 5 to 10 times the weight of yeast to be used, therefore a 25g pack would require a total volume of water+must of 125-250ml. For larger commercial quantities this would not be practical, therefore mixing all the yeast in a standard 10 litre bucket would suffice.

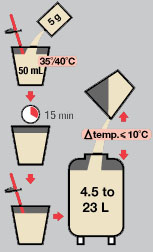

1. Dissolve the dry yeast in 50 ml (2 oz)

of warm NOT HOT water (40°- 43°C or 104°-109°F).

2. Allow to stand for 15 minutes

without stirring.

(DON'T leave for more than 20 mins as this can result in decreased activity of the cells).

3. Then stir well to suspend

all the yeast.

4. Add to previously sulfited must.

Yeast inoculation for white wine

In many of the large wineries, current technology for making white wine often involves clarification of the juice by centrifuging or filtration at low temperatures. This helps to suppress any wild yeast and/or bacterial growth which normally multiply faster at higher temperatures. The juice may also be stored at a low temperature for some considerable time prior to yeast inoculation, followed by a desired cooler temperature fermentation.

Rehydrated yeast should not be added to must at temperatures lower than 15°C - and definitely not below 10°C - if good fermentation characteristics are to be retained. While the rate of fermentation by actively growing yeast can be controlled by decreasing or raising the temperature, yeast cannot tolerate temperature shock.

White wines being made at altitude - cool climate winegrowing - will often be put through a cool fermentation. The benefit of this is to allow the ferment to proceed as slow as possible, and hold onto the delicate flavors and character that is in the grapes grown at these climes. Faster ferments for white wines can happen on those heavier bodied styles where delicacy and subtlety are not required, such as with Meursault or Viognier or occasionally Chardonnay.

Yeast inoculation for red wine

As red wines will still be on their skins, the must will contain a high population of wild yeast of many genera, this includes those species capable of spoilage. The population of yeast in the must will be directly related to the quality of the grapes, the temperature of the must, the use of SO2, and the time the must is held before inoculation. The time of inoculation of red mash depends upon the rate of crushing and filling of the fermenter and whether the must is cool.

Often a fermenter will take longer than half a day to fill. In these cases, the yeast inoculum can be added to a partially filled fermenter as long as the must temperature is above 15°C (certainly not below 10 °C). The total amount of rehydrated yeast required to give 5 million viable cells/ml for the filled fermenter can be added at one addition. Alternatively, rehydrated yeast can be added in several lots during filling of the fermenter.

Do not use an already fermenting must to inoculate a new must:

Some Yeast FAQ's

-

Will SO2 additions affect wine yeast?

Some yeast will be more sensitive to SO2 than other yeasts. In general high SO2 additions may be used to stop the yeast fermentation once the fermentation is complete and the yeast are already in a weakened state.

-

Should I refrigerate or freeze my dry yeast until I use it?

Yes, although dry yeast can be stored at room temperature and performs well for the duration of the shelf life it is preferable to store it at colder temperatures. Dry yeast will always lose some of its viability and activity over time but at colder temperatures these losses are less than at warmer temperatures. If you choose to freeze your dry yeast for storage, let it warm to room temperature in the package before rehydration and addition.

-

Why is rehydrating the dry yeast before adding into the must so important?

Dry yeast needs to be reconstituted in a gentle way. During rehydration the cell membrane undergoes changes which can be lethal to yeast. In order to reconstitute the yeast as gently as possible (and minimize/avoid any damage) yeast producers developed specific rehydration procedures. Although most dry wine yeast will work if added directly, it is recommended to follow the rehydration instructions to insure the optimum performance of the yeast.

-

What will happen to my wine if I add too much or too little yeast?

The addition rate influences the waiting phase and the general fermentation speed as well as the flavour of the finished wine. Adding at too low rates will result in a longer waiting phase and higher risk of contamination as well as longer overall fermentation time (and sometimes stuck fermentations). Adding at too high a rate speeds up the fermentation but can lead to early autolysis.

-

How does changing the fermentation temperature change the "dry" or "fruity" character of the wine?

At warm fermentation temperatures, more esters and higher alcohols are produced than at colder temperatures, resulting in more fruity, floral flavors.

-

Can an open package of dry yeast be resealed and used later?

It is possible, but the important factors are air and moisture. If you can vacuum seal the yeast then this would be ideal, otherwise a re-sealed pack should be used quickly as the cells will lose activity in the presence of air and water. Pressing a pack tightly before applying the seal is not really that effective. Use opened yeast within a week to ensure good performance.

-

Do I need to use nutrients when using dry wine yeast?

Like any yeast, dry wine yeast can benefit from additional nutrients.

Bourgovin RC 212 |

Origin An excellent choice for both young & aged red wines. |

Lalvin Wine Yeast 71B 1122 Yeast 10 Packs (Strange Brew Home-Brew) |

ICV D-47 |

Origin Oenological properties and applications An excellent choice for dry whites, blush wines and residual sugar wines. |

|

71B-1122 |

Origin An excellent choice for blush & residual sugar whites, nouveau & young red wines. Also a good choice for late harvest wines. |

Lalvin Wine Yeast 71B 1122 Yeast 10 Packs (Strange Brew Home-Brew) |

ICV K1V-1116 |

Origin Highly recommended for dry whites, aged reds, and late harvest wines. |

|

EC-1118 |

Origin An excellent choice for champagnes and late harvest wines. Also a very good choice for dry whites. |

|

Lalvin Wine Yeast Usage Chart

| RC 212 | ICV D-47 | 71B-1122 | ICV K1V-1116 | EC-1118 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Whites | * |

**** |

** |

*** |

*** |

| Blush or R.S. Whites | * |

**** |

**** |

** |

** |

| Nouveau | * |

* |

**** |

** |

** |

| Young Reds | **** |

* |

**** |

** |

** |

| Aged Reds | **** |

* |

** |

*** |

*** |

| Champagne Base | * |

* |

* |

** |

**** |

| Secondary Ferment | * |

* |

* |

* |

**** |

| Stuck Fermentations | * |

* |

* |

**** |

**** |

| Late Harvest | * |

* |

*** |

*** |

**** |

| Temp Range (°C) | 20°- 30° |

15°- 20° |

15°- 30° |

10°- 35° |

10°- 30° |

| Fermentation Speed | Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Very Fast |

**** Indicates Strongest Recommendation.